Les presento una entrada reciente que escribí para un foro académico, donde abordo el Medio Oriente, mi postura conservadora como historiador, y el modo correcto de enfrentar el presente.

First and foremost, I must say that William E. Leuchtenburg’s «The Historian and the Public Realm» stands as the most insightful and valuable article I have encountered in my professional development as a public historian. A treasure trove of wisdom on the historical craft, it is filled with indispensable insights and aphorisms that I believe every historian should know.

Regarding the first point in this prompt, if I understand it correctly, I would argue that the Gulf War is a topic of great significance for an informed American audience. My passion for military history is no secret, and I firmly defend its practical relevance. The Gulf War marks the beginning of the Middle East crisis that continues to shape global affairs today. Not only average Americans, but informed Americans too, are deeply ignorant about the Middle East.

For some time now, I have been deeply perplexed by recent developments in the Middle East, you know exactly what I’m referring to. What I find even more astonishing, however, is the fervor with which so many have thrown themselves into political activism over this region. Ask the average partisan, whether they support X or Y, to locate Palestine, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, or Iran on a map, and most would struggle. Yet that hasn’t stopped them from speaking with unwavering conviction. I shall ask all of you: Isn’t that ridiculous?

I am a staunch isolationist, primarily concerned with political developments in my own region, despite the inescapable interconnections of our globalized age. Yet one undeniable truth remains: the past and present conflicts of the Middle East do impact us, precisely because of our misguided interventions in their affairs. Yet the sheer emotional fervor with which most people engage in this debate is absurd. Before declaring absolute convictions, perhaps one should read a serious book, engage in measured discussions, and stop forming opinions based on TikTok slogans, the half-baked rants of your friend Timmy, or the naive idealism that so often accompanies youth and inexperience.

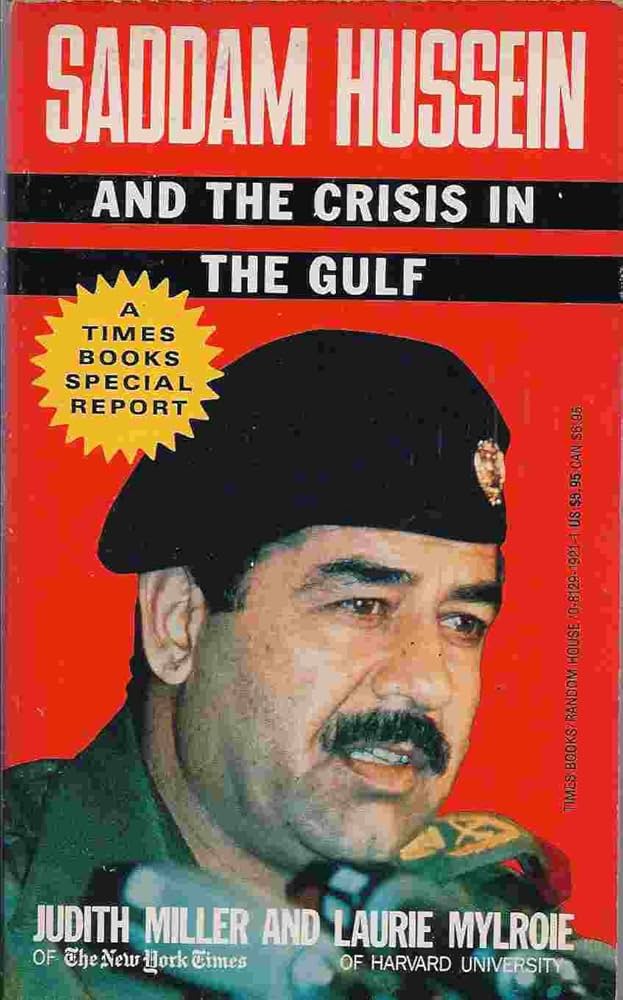

The Gulf War is important to understand because it lies at the center of a debate regarding U.S. interventionism. Whether justified or unjustified, a nuanced understanding of U.S. interventionism is needed. Stay away from absolutes. I am reading a wonderful book to further understand this convoluted topic, and I’ll leave it at that.

To what degree should a public historian attempt to shape public opinion?

Like Leuchtenburg, I’ve engaged with historians who actively intervene in contemporary debates and others who abstain entirely, and like him, I consider these approaches irreconcilable. Consider the official historian of Puerto Rico (the esteemed Dr. Carlos Hernández Hernández), a government-appointed position. His activism (if one can still use the term, given how thoroughly it’s been tarnished in my view) is palpable and valid. At the other extreme stands Cuban military historian Pablo Hernández González, a scholar I’m privileged to know, who deliberately confines his gaze to the distant past. His stance is methodological: only time, he argues, grants the clarity necessary for proper historical study.

Due to my conservative disposition, I tend to remain in the past (in many ways). But occasionally, I erupt into present political contention. When I do, I take care to avoid proselytizing. «You be the judge,» I say, «provided you’ve thoroughly understood all dimensions of the issue.» Again, my biggest issue is the passion with which people defend their weakly built arguments.

Ultimately, I believe public historians should focus primarily on historical divulgation, though there remains room for contemporary debates. To what extent, then, should we seek to shape public opinion? To whatever extent we deem appropriate, so long as we maintain intellectual honesty and a conciliatory spirit. I have seen many historians distort the data they know to be accurate to back up their political positions; this is tragic.

I will add that I vehemently oppose liberalism, communism, socialism, and the fanatical materialism that has infected nearly everyone today. While intellectual growth matters profoundly, so too does mysticism. There is one book in particular I would recommend as essential.

The final question in this prompt (»What role should interpretation play in public history?») has a straightforward answer: interpretation is the very essence of history. Historians don’t merely recount facts; they analyze, contextualize, and inevitably interpret. And from that interpretation springs the never-ending debate: Whose narrative holds weight? Whose perspective deserves prominence? The battle over historical meaning isn’t just academic; it’s a struggle for collective memory itself. History must be understood as a dynamic, never-ending process.

Leuchtenburg, William E. “The Historian and the Public Realm.” The American Historical Review 97, no. 1 (1992): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2164537.